When you take a medication, it sets off on a remarkable journey through your body. From the moment it enters until it exits, countless intricate processes determine whether it will heal, harm, or simply pass through unnoticed. Understanding this journey – the world of Pharmacokinetics, Dosage, and Administration – isn't just for medical professionals; it's empowering knowledge for anyone seeking to optimize their health and get the most out of their prescribed treatments. It’s the difference between a drug working effectively and potentially causing side effects or failing altogether.

This isn't about memorizing complex chemical formulas, but rather appreciating the elegant dance between a drug and your unique physiology. It’s about recognizing why timing, amount, and even the way you take a medication are all critical pieces of your personal health puzzle.

At a Glance: Your Drug's Journey Explained

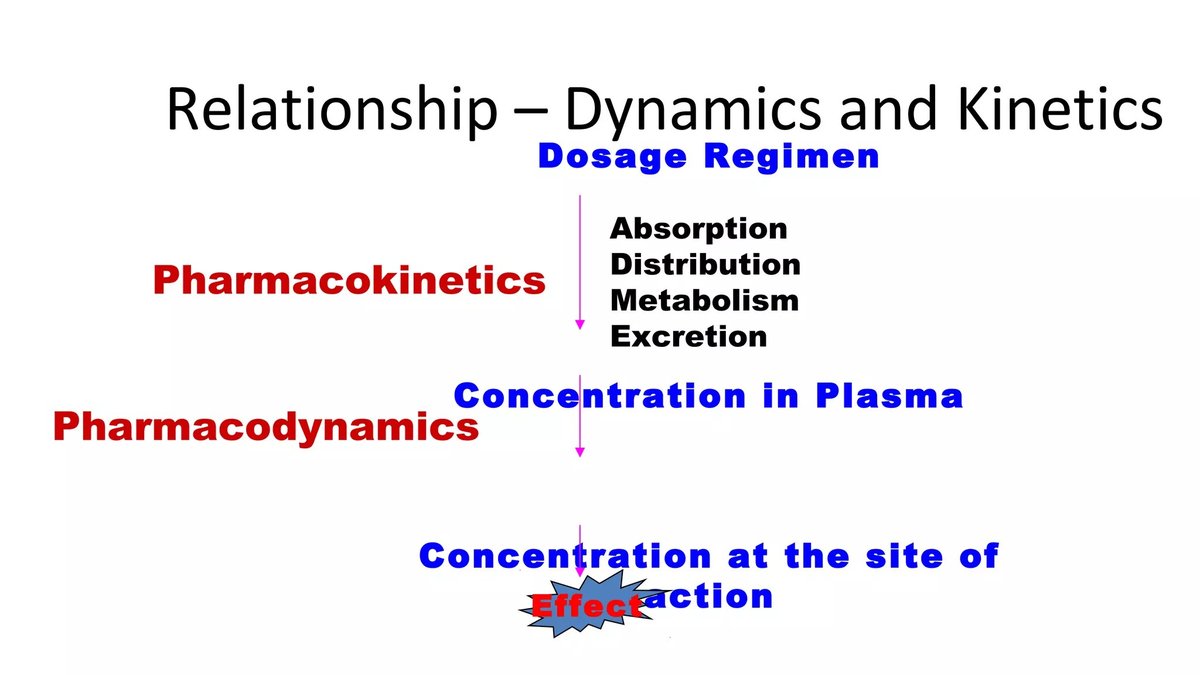

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): How your body acts on a drug. Think of it as the drug's "life cycle" inside you, covering Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME).

- Dosage: The precise amount of a drug given at a specific time. This is carefully calculated to achieve the right therapeutic effect without causing toxicity.

- Administration: The method by which a drug enters your body (e.g., orally, intravenously, topically). This choice significantly impacts how quickly and effectively a drug starts working.

- Why it Matters: These three elements work together to ensure your medication reaches its target, at the right concentration, for the right amount of time, ultimately optimizing treatment success and minimizing risks.

- Personalized Approach: Factors like your weight, age, genetics, and organ function mean that dosages and administration routes aren't "one-size-fits-all."

The Drug's Grand Tour: Unpacking Pharmacokinetics (ADME)

Pharmacokinetics is a fancy word for what your body does to a drug. It's the engine behind whether a medication gets where it needs to go, how long it stays there, and how it eventually leaves. MSD Manuals aptly describes it as the study of "how the body handles a drug," accounting for a four-stage process: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination.

Absorption: The Entry Point

Before a drug can work, it first needs to get into your bloodstream. This initial step is called absorption. Imagine a tiny boat launching into a vast river system; that's your drug getting absorbed.

- Oral Medications: For a pill you swallow, absorption primarily happens in the small intestine, though some can occur in the stomach. The drug must first dissolve, then pass through the intestinal wall into the capillaries.

- Other Routes: If you get an injection, the drug is absorbed from the muscle or under the skin. If it’s intravenous (IV), it bypasses absorption entirely and goes directly into the bloodstream, making it the fastest route to effect.

- What Influences Absorption? Everything from the drug's chemical properties (solubility, size) to your body's conditions (stomach acidity, presence of food, blood flow to the absorption site) can affect how well and how quickly a drug is absorbed.

Distribution: Spreading the Word

Once in the bloodstream, the drug is like a message being circulated throughout the body. Distribution describes how the drug travels from your blood to various tissues and organs, eventually reaching its target site where it can exert its therapeutic effect.

- Blood Flow: Areas with rich blood supply, like your heart, liver, and kidneys, receive drugs more quickly than areas with poorer supply, such as fat tissue or bones.

- Tissue Barriers: Some areas have natural barriers. The blood-brain barrier, for example, is a highly selective filter that protects your brain, meaning only certain drugs can cross it to treat conditions like meningitis.

- Protein Binding: Many drugs bind to proteins in your blood plasma. Only the "unbound" drug can leave the bloodstream and interact with target cells. This binding can act as a reservoir, slowly releasing the active drug over time.

- Factors at Play: Your body composition (fat-to-muscle ratio), organ size, and even disease states can alter how a drug distributes.

Metabolism: The Chemical Transformation

Metabolism is your body's way of chemically altering drugs, often to make them easier to eliminate. Think of it as a processing plant, converting raw materials into more manageable forms.

- The Liver's Role: Your liver is the primary metabolic powerhouse. Enzymes in liver cells break down most drugs. Sometimes, this process converts an inactive drug into an active form, or transforms an active drug into inactive byproducts (metabolites).

- First-Pass Effect: For many orally administered drugs, a significant portion is metabolized by the liver before it even reaches general circulation. This "first-pass effect" can drastically reduce the amount of active drug available to the body.

- Genetic Variations: Our genetic makeup can influence the activity of metabolic enzymes. This is why some individuals process drugs very quickly, requiring higher doses, while others metabolize them slowly, needing lower doses to avoid toxicity. This personalized aspect is a cornerstone of modern pharmacotherapy.

- Drug Interactions: Taking multiple medications can sometimes overload or induce these metabolic enzymes, leading to one drug affecting the metabolism of another, often with significant clinical consequences.

Elimination: Saying Goodbye

The final act in the pharmacokinetic drama is elimination – the removal of the drug and its metabolites from your body.

- Kidney Excretion: Your kidneys are the main route for drug elimination. They filter waste products and drugs from the blood, which are then excreted in urine.

- Other Routes: Some drugs are eliminated through bile (and then feces), exhaled through the lungs (like alcohol), or even secreted in sweat, saliva, or breast milk.

- Organ Function: The efficiency of your kidneys and liver directly impacts how quickly drugs are eliminated. Impaired organ function (e.g., kidney disease) means drugs stay in your system longer, necessitating dose adjustments to prevent accumulation and toxicity.

- Half-Life: A key concept in elimination is a drug's "half-life" – the time it takes for the concentration of a drug in the body to reduce by half. This helps determine how often a drug needs to be taken to maintain a steady, effective level.

Crafting the Perfect Dose: The Art and Science of Dosage

Dosage is more than just how many pills you take; it’s the meticulously calculated quantity of a drug required to achieve a therapeutic effect without causing undue harm. It's a critical balance, ensuring there's enough drug to be effective but not so much that it becomes toxic.

Why Dosage is a Delicate Balance

Every drug has a "therapeutic window" – a range of concentrations in the body where it's most effective and least harmful.

- Too Little, Too Late: A dose below the therapeutic window won't have the desired effect. It's like trying to put out a bonfire with a water pistol.

- Too Much, Too Risky: A dose above the therapeutic window can lead to adverse effects, ranging from mild discomfort to severe, life-threatening toxicity.

The goal is always to keep the drug concentration within this optimal window for the duration of the treatment.

Initial vs. Maintenance Doses

- Loading Dose: Sometimes, to quickly achieve the desired therapeutic concentration, especially for drugs with long half-lives or in urgent situations, a larger initial "loading dose" is given. This rapidly gets the drug into the effective range.

- Maintenance Dose: After the loading dose, or if a loading dose isn't needed, smaller "maintenance doses" are given regularly to keep the drug's concentration within the therapeutic window as the body metabolizes and eliminates it.

Factors that Fine-Tune Your Dose

While a drug's manufacturer provides standard dosing guidelines, your healthcare provider tailors these to your unique circumstances. This personalization is where pharmacokinetics truly shines, as highlighted by JBClinPharm's insights into advances in personalized drug delivery and pharmacogenomics.

- Body Weight and Surface Area: For many drugs, especially in children or for potent medications, doses are calculated based on weight (mg/kg) or even body surface area to ensure proportionality.

- Age: Infants and the elderly often have different pharmacokinetic profiles. Infants have immature liver and kidney function, while older adults may have reduced organ function, slower metabolism, and altered distribution due to changes in body composition.

- Organ Function (Liver/Kidney): As discussed under metabolism and elimination, impaired liver or kidney function means drugs stay in the body longer. Doctors must reduce doses or extend the dosing interval to prevent accumulation.

- Genetic Makeup: "Pharmacogenomics," the study of how genes affect a person's response to drugs, is revolutionizing dosing. Genetic variations can significantly alter how you metabolize certain drugs, affecting efficacy and the risk of side effects.

- Disease State: Certain illnesses can alter drug kinetics. For example, severe burns can increase drug elimination, while heart failure can reduce blood flow to organs, affecting distribution and metabolism.

- Drug-Drug Interactions: When two or more drugs are taken together, they can influence each other's ADME processes, requiring dose adjustments. This is why it's crucial to inform your doctor and pharmacist about all medications, supplements, and even herbal remedies you're taking.

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): For drugs with a narrow therapeutic window, doctors may order blood tests to measure the drug's concentration in your system. This allows for precise dose adjustments to ensure optimal levels are maintained.

Routes and Rhythms: Mastering Drug Administration

The way a drug enters your body – its route of administration – is a fundamental decision that profoundly impacts its effectiveness, speed of action, and potential side effects.

Common Routes and Their Impact

- Oral (By Mouth): The most convenient and common route. Pills, capsules, liquids.

- Pros: Easy, non-invasive, often cost-effective.

- Cons: Slower onset of action, subject to first-pass metabolism, absorption can be variable (influenced by food, stomach pH), can cause gastrointestinal upset.

- Intravenous (IV - into a vein): Directly into the bloodstream.

- Pros: Fastest onset of action, 100% bioavailability (no absorption issues), precise dosing control, suitable for drugs that irritate muscles or can't be absorbed orally.

- Cons: Requires professional administration, risk of infection, pain at injection site, immediate adverse reactions possible, more invasive.

- Intramuscular (IM - into a muscle): Injected into muscle tissue (e.g., deltoid, gluteus).

- Pros: Faster absorption than subcutaneous due to good blood supply, suitable for larger volumes than subcutaneous, allows for sustained release for some drugs.

- Cons: Pain, bruising, risk of nerve damage, slower than IV.

- Subcutaneous (SC - under the skin): Injected into the fatty layer just beneath the skin.

- Pros: Slower and more sustained absorption than IM, good for drugs that need a slower release (e.g., insulin), less painful than IM for small volumes.

- Cons: Limited volume can be administered, potential for local irritation.

- Topical (On the skin): Creams, ointments, patches.

- Pros: Local effect, minimizes systemic side effects, convenient (patches for sustained release).

- Cons: Absorption can be poor or inconsistent, not suitable for systemic effects (unless designed as a transdermal patch).

- Inhaled (Into the lungs): Sprays, nebulizers.

- Pros: Rapid local effect for respiratory conditions, some systemic absorption is possible.

- Cons: Requires proper technique, can irritate airways.

- Rectal (Suppositories): Into the rectum.

- Pros: Useful for local effect, or if oral route is not possible (vomiting, unconsciousness), avoids some first-pass metabolism.

- Cons: Absorption can be irregular, patient discomfort.

The Rhythm of Dosing: Why Timing Matters

Beyond the route, when and how often you take a drug are crucial for maintaining consistent therapeutic levels.

- Maintaining Steady State: Regular dosing aims to achieve a "steady state," where the amount of drug entering the body equals the amount being eliminated, keeping the drug concentration within the therapeutic window.

- Meal Timing: Some drugs are better absorbed on an empty stomach, while others cause less irritation or are better absorbed with food. Always follow specific instructions.

- Adherence: Missing doses or taking them at irregular intervals disrupts the steady state, leading to fluctuating drug levels that can diminish efficacy or increase side effects. This applies to various medications, including those discussed in an Oral third-generation cephalosporin guide, where consistent administration is key for battling bacterial infections.

Beyond the Basics: Cutting-Edge Advances in PK/PD

The field of pharmacokinetics isn't static; it's a dynamic area of research constantly evolving to make drug therapy safer and more effective. Recent advancements, as highlighted by JBClinPharm, are transforming how we think about drug delivery and dosage.

Smart Delivery Systems: Getting Drugs Exactly Where They're Needed

Traditional drug forms often face hurdles like poor solubility, limited bioavailability, and inconsistent absorption. Novel drug delivery technologies are addressing these challenges head-on.

- Nanoparticles, Liposomes, and Micelles: These microscopic carriers can encapsulate drugs, protecting them from degradation in the body and facilitating targeted delivery. Imagine a tiny, intelligent drone delivering its cargo only to specific cells or tissues.

- Enhanced Efficacy, Reduced Side Effects: For instance, nanoparticle-based systems have shown immense promise in oncology. By encapsulating chemotherapy drugs, researchers can achieve sustained release, prolonging the drug's circulation time and enhancing its accumulation at tumor sites. This means more drug goes to the cancer, and less to healthy tissues, leading to improved anti-tumor activity and reduced systemic toxicity.

- Overcoming Bioavailability Issues: For drugs that are poorly absorbed orally, these advanced systems can significantly improve their "bioavailability" – the proportion of a drug that enters the circulation and can have an active effect.

Predictive Power: Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Simulation

Computational tools are becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing researchers and clinicians to predict drug behavior in vivo (within a living organism) and optimize dosing regimens before they are even tested extensively in humans.

- Population Pharmacokinetics: This approach analyzes drug concentration data from many individuals to understand the typical pharmacokinetic profile of a drug and identify factors causing variability, such as age, gender, or disease state. This data helps develop generalized dosing guidelines.

- Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: PBPK models are like virtual human bodies. They integrate physiological and biochemical data (e.g., organ blood flow, tissue permeability, metabolic pathways) to simulate how a drug will move through and be processed by the body. These models can predict drug concentrations in different tissues over time, assessing the impact of drug-drug interactions, organ dysfunction, and genetic variations on drug exposure.

- Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) Modeling: This takes PK a step further by linking drug concentration (PK) with its observed effect (pharmacodynamics, or PD). By understanding the relationship between how much drug is present and what effect it has, PK-PD models help establish therapeutic targets and fine-tune dosing regimens to achieve desired clinical outcomes while minimizing the risk of toxicity.

The Future is Personal: Precision Medicine

The ultimate goal of these advancements is personalized medicine. By leveraging an individual's unique characteristics – genetics, physiology, disease state – researchers can design customized drug formulations and dosing strategies that optimize drug exposure and response. This means maximizing therapeutic outcomes for you, while minimizing adverse effects specific to your body. Pharmacogenomics, for example, is enabling doctors to prescribe the right drug at the right dose, right from the start, significantly improving patient outcomes.

Why This Matters to YOU: Optimizing Your Drug Therapy

Understanding pharmacokinetics, dosage, and administration isn't academic; it's practical knowledge that empowers you to be an active participant in your healthcare.

Your Role in Medication Safety and Efficacy

- Be a Knowledge Seeker: Don't hesitate to ask your doctor or pharmacist questions about your medications. How should I take it? With food? At what time? What are potential interactions?

- Follow Instructions Diligently: This isn't just about compliance; it's about respecting the precise science behind your medication. Skipping doses, taking more or less than prescribed, or altering the route of administration can throw off the delicate balance of drug levels in your body.

- Maintain an Accurate Medication List: Keep an up-to-date record of all medications (prescription, over-the-counter, supplements, herbal remedies) you are taking and share it with every healthcare provider. This is crucial for avoiding dangerous drug-drug interactions that can alter pharmacokinetics.

- Report Side Effects: Your body's response to a drug is unique. If you experience unexpected or severe side effects, report them promptly. This information helps your doctor adjust your dosage, switch medications, or explore alternative administration routes.

Addressing Common Questions & Misconceptions

"Why does my dose keep changing?"

Doses can change for many reasons: your body's response, changes in your weight, development of new medical conditions (especially affecting liver or kidney function), the addition of new medications that might interact, or simply to find the optimal therapeutic window. It's a sign your healthcare provider is actively managing your treatment.

"Can I split my pills to save money or take a smaller dose?"

Only if your pills are scored (designed to be split) and your doctor or pharmacist explicitly tells you it's okay. Unscored pills may not contain an even distribution of the drug, leading to inaccurate doses. Some pills have special coatings (e.g., enteric coating, extended-release) that are destroyed when split, altering their pharmacokinetics and potentially causing rapid absorption or stomach irritation.

"Does generic medicine work the same as brand-name?"

Yes, legally, generic drugs must be "bioequivalent" to their brand-name counterparts. This means they deliver the same amount of active ingredient to the bloodstream over the same period, ensuring identical pharmacokinetic profiles and therapeutic effects. Any minor differences are usually in inactive ingredients, which typically don't affect drug action.

"Why do some drugs have so many side effects, and others hardly any?"

Side effects are often related to a drug's mechanism of action and how widely it distributes in the body. If a drug acts on receptors that are present in many different tissues, it can cause effects beyond its intended target. The dose, your individual pharmacokinetics, and even genetic predispositions can all influence the likelihood and severity of side effects.

Partnering for Health: Taking Control of Your Medication Journey

Your body is an incredibly complex system, and introducing a medication is a significant event. By understanding the fundamentals of pharmacokinetics, dosage, and administration, you transform from a passive recipient of treatment to an informed and empowered partner in your health.

Remember, every prescription, every dose, and every administration route is a carefully considered decision by your healthcare team. Your active engagement – asking questions, providing accurate information, and adhering to instructions – is crucial for making that decision the right one for you. This collaborative approach ensures that your medications don't just work, but work optimally, guiding you toward better health and a higher quality of life.