When a bacterial infection takes hold, choosing the right antibiotic isn't just a clinical decision; it's a strategic one. Among the arsenal of anti-infectives, oral third-generation cephalosporins stand out, offering a versatile and potent option for a range of community-acquired infections. This guide provides a comprehensive Overview and Classification of Oral Third-Generation Cephalosporins for Clinical Practice, designed to equip you with the knowledge needed to leverage these critical medications effectively and responsibly.

Think of these drugs as a refined tool in the beta-lactam family, engineered for broader reach and greater stability against bacterial defenses. They bridge the gap between earlier generations, which focused more on Gram-positive bacteria, and newer agents, offering a valuable balance for many common pathogens.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways for Oral Third-Generation Cephalosporins

- What they are: A class of beta-lactam antibiotics derived from Acremonium fungus, known for their bactericidal action.

- How they work: They disrupt bacterial cell wall formation by inactivating penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), leading to cell death.

- Key oral drugs: Cefdinir, Cefixime, and Cefpodoxime proxetil are the primary oral formulations.

- Spectrum of activity: Excellent against many Gram-negative bacteria, improved stability against beta-lactamase enzymes, but less potent against Staphylococcus aureus compared to first-generation cephalosporins.

- Common uses: Community-acquired respiratory tract infections (e.g., otitis media, sinusitis, bronchitis, pneumonia), uncomplicated urinary tract infections, and certain skin/soft tissue infections. Also used for uncomplicated gonorrhea.

- Important considerations: Generally well-tolerated, but common side effects include GI upset. Cross-allergy risk with penicillin is lower than with earlier generations. Responsible use is crucial to combat antibiotic resistance.

Understanding the Cephalosporin Family: A Quick Primer

Cephalosporins are a venerable class of beta-lactam antibiotics, first isolated from the fungus Acremonium. Their defining characteristic, much like their penicillin cousins, is the beta-lactam ring structure, which is central to their antibacterial activity. What sets cephalosporins apart, however, is their classification into "generations." This isn't just an arbitrary grouping; it reflects a progressive enhancement in their spectrum of activity and stability against bacterial resistance mechanisms.

With each successive generation, these antibiotics have generally become more potent against Gram-negative bacteria and more resistant to beta-lactamase enzymes—bacterial defenses that can dismantle the crucial beta-lactam ring. The first generation mostly targets Gram-positive cocci, while the second generation expands coverage to some Gram-negative species. The third generation, our focus here, represents a significant leap forward, offering a broader and more powerful effect against a wider array of common pathogens, particularly those causing respiratory and urinary tract infections.

The Science Behind the Cure: Mechanism of Action

At their core, oral third-generation cephalosporins are bactericidal agents, meaning they directly kill bacteria rather than just inhibiting their growth. Their modus operandi is elegantly destructive: they interfere with the formation of the bacterial cell wall, a vital protective structure that maintains the integrity of the bacterial cell.

Specifically, these antibiotics bind to and inactivate a group of enzymes known as Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs). PBPs are crucial for synthesizing peptidoglycan, the main structural component of the bacterial cell wall. They cross-link peptidoglycan strands, essentially building and repairing the wall. By blocking these PBPs, third-generation cephalosporins prevent the formation of a stable, robust cell wall. This structural compromise leaves the bacterial cell vulnerable to osmotic lysis—it swells and bursts due to the influx of water—leading to bacterial cell death.

Furthermore, third-generation cephalosporins exhibit improved stability against many beta-lactamase enzymes produced by bacteria. This increased stability is what gives them their broader spectrum of activity, especially against many Gram-negative bacteria that might otherwise be resistant to earlier beta-lactam antibiotics. It's a key reason why they are so often chosen for infections where these resistant strains might be present.

Key Players: Oral Third-Generation Cephalosporins in Practice

When we talk about oral third-gen cephalosporins, three names frequently come to mind:

- Cefdinir: A widely used oral cephalosporin with good activity against common respiratory pathogens. It's often prescribed for acute otitis media, sinusitis, pharyngitis/tonsillitis, and community-acquired pneumonia.

- Cefixime: Notable for its prolonged serum half-life, which allows for once-daily dosing. Cefixime is particularly effective against a wide range of Gram-negative bacteria and is a go-to choice for uncomplicated urinary tract infections. It's also specifically indicated for uncomplicated gonorrhea.

- Cefpodoxime proxetil: This is a prodrug, meaning it's inactive until metabolized in the body. Once activated, it provides broad-spectrum coverage against many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, making it suitable for similar indications as Cefdinir, including respiratory tract and urinary tract infections.

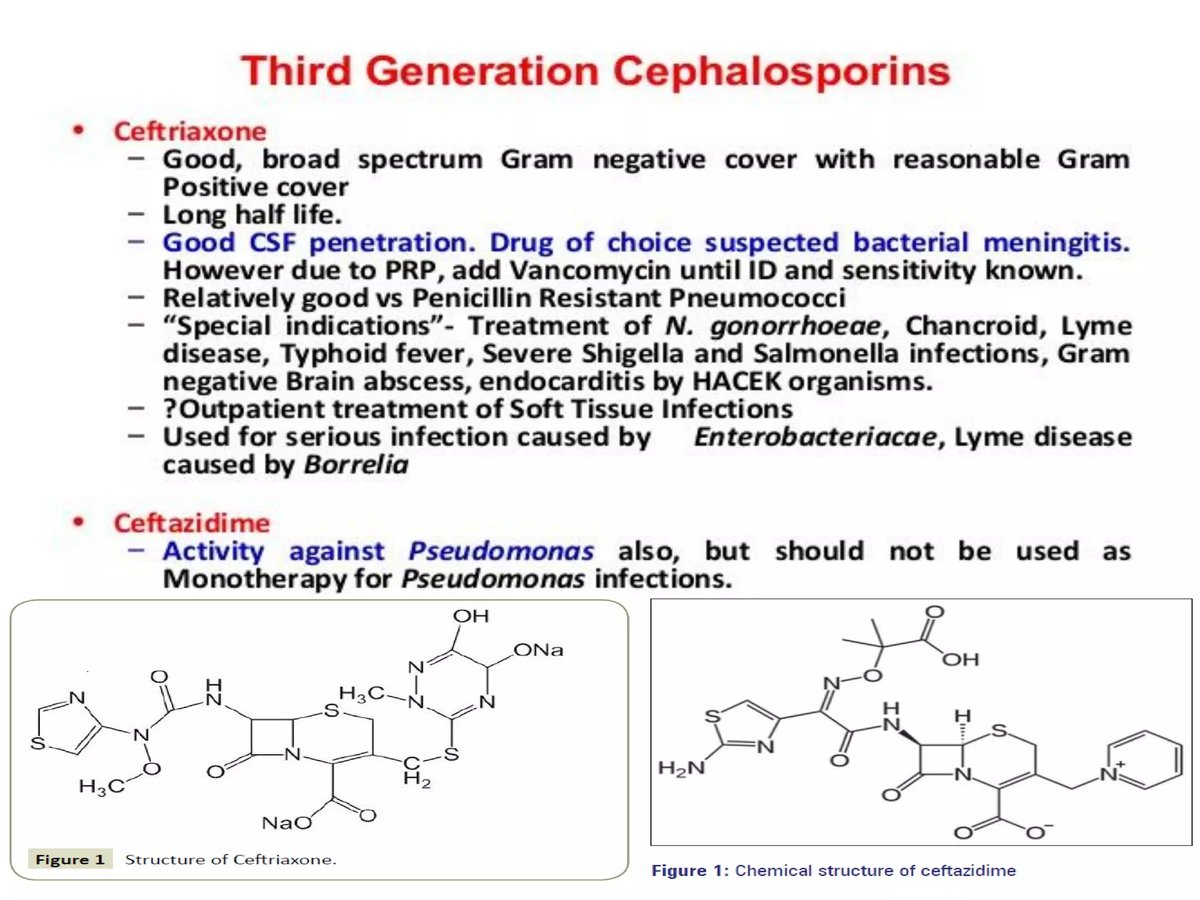

While our focus here is on the oral forms, it's worth noting that the third-generation class also includes powerful intravenous agents like Cefotaxime, Ceftriaxone, and Ceftazidime. These IV counterparts often serve as the initial therapy for more severe infections, with the oral drugs then used for step-down therapy to complete the course of treatment at home. For example, Ceftriaxone, an IV agent, is known for its long half-life enabling once-daily dosing and its utility in conditions like gonorrhoea, pelvic inflammatory disease, epididymo-orchitis, and as an alternative for suspected meningitis (all third-generation cephalosporins, except cefoperazone, can penetrate the cerebrospinal fluid, though the oral forms are not typically used for meningitis).

The Reach of Third-Generation Cephalosporins: Spectrum of Activity

Oral third-generation cephalosporins offer a valuable balance in their antibacterial spectrum. They are generally recognized for:

- Excellent Gram-Negative Coverage: They are highly effective against a broad range of Gram-negative bacteria, including Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and many Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus mirabilis). This makes them particularly useful for respiratory, urinary, and intra-abdominal infections.

- Improved Beta-Lactamase Stability: As mentioned, they possess enhanced stability against many common beta-lactamase enzymes, which helps them retain efficacy where earlier generations might fail.

- Moderate Gram-Positive Coverage: While not as potent against Staphylococcus aureus as first-generation cephalosporins, they still provide decent activity against many streptococcal species, including Streptococcus pneumoniae (a common cause of pneumonia and otitis media). However, they are not typically the first choice for known methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.

- Antipseudomonal Activity (IV forms): It's important to distinguish that while the class of third-generation cephalosporins includes agents with antipseudomonal activity (e.g., IV Ceftazidime), the oral third-generation cephalosporins generally do not provide reliable coverage against Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

This broad yet specific spectrum means they are well-suited for empiric therapy when the exact pathogen isn't yet identified, especially in community-acquired settings where typical pathogens are expected.

When to Prescribe: Clinical Applications and Indications

Oral third-generation cephalosporins fill an important niche in clinical practice, often chosen when first-line antibiotics are unsuitable (e.g., due to resistance patterns or patient allergies) or for specific infections where their spectrum of activity is particularly beneficial.

They are primarily used to treat mild to moderate bacterial infections, especially those acquired in the community. Key indications include:

- Respiratory Tract Infections (RTIs):

- Acute Otitis Media (AOM): Inflammation of the middle ear, commonly seen in children.

- Acute Maxillary Sinusitis: Inflammation of the sinus cavities.

- Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis (AECB): Worsening of chronic lung disease, often triggered by bacterial infection.

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP): Lung infection contracted outside of a hospital setting.

- Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Infections affecting the bladder or urethra without structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract.

- Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: For certain non-severe infections, particularly when streptococcal species are suspected.

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs):

- Uncomplicated Gonorrhea: Cefixime (oral) and Ceftriaxone (intramuscular) are standard treatments for this common STI.

- Step-Down Therapy: For more severe infections initially treated with intravenous antibiotics, oral third-generation cephalosporins can provide a smooth transition to complete the treatment course at home, reducing hospital stays and healthcare costs. This is common for conditions like bacteremia/septicaemia, bone and joint infections, and complicated intra-abdominal infections, where the oral route can effectively consolidate recovery.

They are also a viable alternative for patients with a documented penicillin allergy, especially those with non-severe, delayed hypersensitivity reactions. The risk of cross-reactivity between third-generation cephalosporins and penicillin is significantly lower than with earlier generations, making them a safer option in many cases.

Navigating Potential Pitfalls: Adverse Effects and Interactions

Like all medications, oral third-generation cephalosporins come with potential side effects and drug interactions. Generally, they are well-tolerated, but awareness of these issues is crucial for patient safety and effective treatment.

Common Adverse Effects

Most side effects are mild and transient, primarily affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) system:

- Gastrointestinal Disturbances: This is the most common category, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Diarrhea often occurs due to the disruption of the normal bacterial balance in the gut.

- Hypersensitivity Reactions: Skin rashes and itching (urticaria) are frequent. More severe allergic reactions, such as anaphylaxis (characterized by difficulty breathing, swelling, and a sudden drop in blood pressure), can occur but are rare. It's important to reiterate that the risk of cross-allergy with penicillins is lower with third-generation cephalosporins compared to first or second generations, making them a safer alternative for many penicillin-allergic patients.

Serious, Yet Rare, Adverse Effects

While infrequent, certain serious side effects warrant immediate medical attention:

- Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea (CDAD): All antibiotics, including cephalosporins, can disrupt the gut microbiome, leading to an overgrowth of Clostridium difficile. This can cause severe, watery, or bloody diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis. Patients experiencing such symptoms should seek immediate medical care.

- Drug-Induced Hemolytic Anemia: A rare condition where the immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys red blood cells.

- Seizures: This risk is higher in patients with pre-existing kidney disease, as the drug can accumulate to toxic levels. Dosage adjustments are critical in renal impairment.

- Transient Liver Enzyme Elevations: Mild and usually reversible increases in liver enzymes can occur, though significant liver injury is rare.

- Injection Site Inflammation: (Relevant for IV forms) Pain, redness, or swelling at the injection site can occur.

Drug Interactions to Watch For

The most notable drug interaction for oral third-generation cephalosporins involves antacids containing aluminum or magnesium. These antacids can significantly reduce the absorption of oral cephalosporins, thereby lowering their effectiveness. It's generally recommended to administer oral cephalosporins at least two hours before or after antacids.

Additionally, certain cephalosporins (particularly older IV agents like Cefoperazone, which is now discontinued in many regions) have been associated with bleeding abnormalities due to interference with vitamin K metabolism, but this is less common with the oral third-generation agents discussed here.

The Imperative of Responsible Antibiotic Use

In our ongoing battle against bacterial infections, few principles are as critical as responsible antibiotic stewardship. The rise of antibiotic resistance is a global health crisis, and every prescribing decision impacts its trajectory.

For oral third-generation cephalosporins, this means:

- Confirm Bacterial Infection: These drugs are ineffective against viral infections (like the common cold or flu). Prescribing them for non-bacterial illnesses not only fails to help the patient but also contributes to resistance. Diagnostic confirmation of a bacterial infection is ideal where feasible.

- Complete the Full Course: Patients must be educated to complete the entire prescribed course of antibiotics, even if they start feeling better. Stopping early can allow resistant bacteria to survive and multiply, leading to recurrence and future treatment failures.

- Avoid Overuse and Misuse: Using broad-spectrum antibiotics like third-generation cephalosporins when a narrower-spectrum agent would suffice, or for minor infections that might resolve on their own, hastens the development of resistance. Always choose the most targeted effective agent.

- Follow Dosing Instructions Carefully: Incorrect dosing, especially rapid bolus administration of IV agents like Cefotaxime (which can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias), underscores the importance of adhering strictly to administration guidelines. For oral forms, this means correct timing relative to food and other medications.

As healthcare professionals, we hold a vital responsibility in preserving the efficacy of these essential medications. By judiciously applying our knowledge of their spectrum, indications, and potential downsides, we can ensure that oral third-gen cephalosporins remain a powerful and reliable tool for generations to come.

Empowering Your Practice with Informed Decisions

Navigating the landscape of antibiotic therapy requires both deep understanding and judicious application. Oral third-generation cephalosporins represent a sophisticated and highly effective class of antibiotics, perfectly suited for a range of common bacterial infections, particularly when enhanced Gram-negative coverage or beta-lactamase stability is needed.

By understanding their mechanism of action, specific oral agents (Cefdinir, Cefixime, Cefpodoxime proxetil), broad spectrum of activity, and critical clinical indications, you can confidently integrate them into your treatment strategies. Remember to always consider potential adverse effects, drug interactions (especially with antacids), and the paramount importance of antibiotic stewardship. Every informed decision you make strengthens our collective ability to combat infectious diseases effectively and responsibly.